«I was at home at the time. Which is 450 metres’ from the Belle Equipe, where unfortunately 18 people died», says Simone Tondo, from Sardinia, who arrived in Paris a few years ago, and conquered the city with his bistro Roseval, closed a few months ago. He’s speaking of the terrible night on 13th November. Giovanni Passerini, from Rome, has also been living in Paris for a few years now, and here, after the great success he got with Rino, he’s about to open a new restaurant, Céros. He was also at home: «I live right where the attacks took place: it basically happened between my home and where once was Rino».

Brazilian Mauricio Zillo, who conquered everyone in Milan with the cooking offered at Rebelot, returned to Paris a few months ago to open his A Mere: «It was 9.30 pm, right in the middle of the dinner service. Some people had already eaten, some were coming. Next to us there’s another bistro and the manager was outside, in the street, smoking. He then came to our place, nervous, and told us he had just heard there were some attacks taking place in Paris».

Simone, Giovanni and Mauricio are three excellent chefs, we met them in Italy and we’re proud of their success in Paris. Thinking of them in the hours and days following the terrible attacks was automatic. Listening to their stories, their thoughts, helps us understand what happened and most of all how the city reacted after such bloody and brutal acts.

We saw a photo, a few hours after the most agitated news on the night of Friday 13th September, published on Mauricio Zillo’s Facebook page who said he locked himself inside the cellar of his restaurant with 28 clients: «When we realised we had to close straight away, we tried, keeping calm, to tell our clients to go down into the cellar, explaining that terrible things were going on less than one kilometre from us. I closed the restaurant and we went downstairs. And we started to open bottles: it was a horrible time but we couldn’t just start to cry. We drank, we didn’t ask anyone to pay, we tried to spend that moment of tension together, united».

The photo Mauricio Zillo posted on his Facebook page on Friday 13th November with his clients hiding in the cellar of his restaurant

The tension was instead much different for

Giovanni Passerini: «At one point I saw the news of the attack at restaurant

Carillon. I knew my wife was dining in another restaurant but very close. I couldn’t get in touch with her and meanwhile more scary details arrived in the news. A little later, thank god, she managed to return home with a taxi, even though she was only 150 metres from home».

Yet the memories of that night will long remain: «It’s something I can’t get out of my mind - continues

Passerini – I recognised, among the photos of those who died that night, the faces of

Rino’s clients. It touched..."us". The fact I or

Mauricio, or

Simone weren’t there is a detail. And even though perhaps this shouldn’t be the case, when something happens so close in this way, you feel it even stronger. It’s difficult to get such unprecedented violence out of your head».

On Friday night in Paris they didn’t hit the symbols the entire world knows. Terrorists hit young and popular neighbourhoods, which were once inhabited by the working class, and where there is a real cohabitation of French people and citizens with different religions and cultures. Entertainment, cultural, convivial places. «I feel they wanted to hit a very young area, even though it is rather bourgeois», says

Simone Tondo.

Passerini’s analysis is more articulated and grave: «These attacks arrived very close to my area and strike me a lot, but I must say I’m not that surprised because integration policies in France and especially in Paris are a real failure. Social tensions are profound. The X and XI arrondissement are mixed neighbourhoods in terms of ethnicity, where you can notice some social differences, they’re palpable. And they’re even quite close to some banlieue: I’m almost certain those who were shooting on Friday knew very well where to hit».

Carillon, in Canal Saint-Martin, the day after the disaster

Yet it is now the moment to react. And this, in the eyes of

Simone Tondo, is already taking place: «I believe the French are really capable of uniting and reacting together, defending their liberty when necessary. It is clear this city wants to live. Of course people are scared. And for sure, as in the aftermath of the

Charlie Hebdo attack, restaurants in town will work less».

Especially those who rely on tourism, according to

Mauricio Zillo: «Many tourists who were to come, are cancelling their programmes: restaurants based on that will strive. But I live in that neighbourhood and while on Saturday and Sunday night there were really few people around, on Monday at our place and not only there, it seemed like it was Saturday night. We were packed, and people stayed until three in the morning, drinking and having fun with us. It was as though people wanted to take back the Friday that was stolen from them, to speak with others and tell their story».

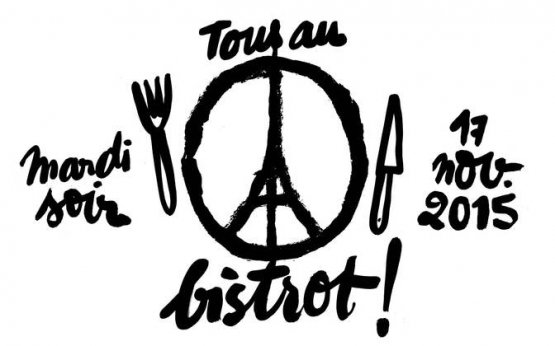

A picture of the Tour Eiffel transformed into the symbol of peace, created by graphic designer Jean Jullien, has become the logo of "Tous au bistrot", the event launched by Le Fooding inviting everyone in Paris to fill up restaurants last Tuesday night

’s feeling is bitterer: «I don’t think it is right to say "we are not scared". We must learn to live with it, but we shouldn’t deny it. I am scared. And not only to be the victim of an attack, but of the world in which I will have to live, of people’s reactions, of the exasperation of social conflict. To be honest, today I face the imminent opening of my restaurant thinking I cannot move back. I invested all I have in a restaurant in the XI arrondissement, of course today it’s hard for me. I hope when the restaurant will be open the joy of doing something beautiful, and of following my passion, will make me look at things in a different way».

And while these preoccupations are real, sincere and very understandable, we like to believe

Mauricio Zillo’s optimism can be the best way, a week after that deadly night, to send our warm and sympathetic thoughts to all of Paris: «I moved to this neighbourhood because it’s always lively, even at night. I returned to Paris for this reason and I believe we need to feel responsible to keep this city alive, to keep on living. I see a great solidarity emerging in a place which, just like all other metropolises around the world, can also be cold and hard. In the tragedy, this is the nice thing to see: people remember they’re part of a community, of a city based on sharing public spaces. And helping each other. Reclaiming their freedom».